We all need to categorize our information. I'm not talking about carrying an agenda or notebook with you but something that your brain does for you automatically; otherwise you would be buried under information overload. Our brain has different departments if you will where all the info is stored, and they are called “schemata.”

A schema, as Piaget has stated, is the category we build for a specific item. For example, the schema “dog” would include all the necessary information and trivia, characteristics, even personal opinions and experiences related to the topic of dogs. Anything remotely canine goes into that department.

It is something we do since childhood, and we need to assimilate and accommodate incoming data. That means our schemata could grow by incorporating additional information about the topic in question. This is something that helps us activate a schema and gain more knowledge about a specific topic. It is a process called assimilation, and we are glad that our schema has grown and gotten more complex. This is what we experience when we learn something new and welcome that new knowledge.

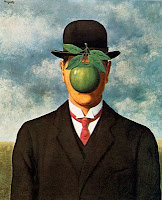

However, a problem may occur when the incoming data is not conforming to our already existing schema. That is we would need to “accommodate” information that is at odds with our previously held beliefs and assumptions. That's when we might experience a serious problem. It's when you think that dogs are cute and peaceful when suddenly one of them bites your hand for no apparent reason whatsoever. Your schema is then shaken up.

Still we often have an innate tendency to protect our own beliefs and will even use defense mechanisms to do so. It causes stress to abandon what we thought to be correct and replace it immediately with a new schema. Of course, it depends on the topic in question and your affective response to it. You can ignore the biting dog and attribute it to a single random case of violence, yet still hold intact your belief that dogs are cute, fluffy, and harmless.

When there is no strong emotional tie to the schema, it is easier to abandon or change it. If somebody tells you cats are not as loyal as dogs whereas you used to believe it to be the case, your reaction might not be stressful. You will embrace the new information and simply change your schema.

But when it comes to more personal issues, then it is another story. If somebody tells you that your partner, whom you believed to be loyal, is seen holding hands with another person, then you most likely would feel distress. You may accept the information and reformulate your schema, “my partner is not as loyal as I thought him or her to be,” or you simply deny the facts and stick to your own schema, ignoring your friend's comments or even attacking him or her for making such outrageous claims.

It would be even more painful if it is a long-held cherished belief. Imagine you spent all your life with specific religious or political beliefs and suddenly realize that you were wrong, that your previous outlook has been shattered and you need to change your view. It is probably a common fact that elderly people tend to be more conservative than younger people, for the latter still have fresh and dynamic schemata and a complete changeover would not cause them as much pain as to those who have invested and poured years (and energy and perhaps money) into that belief.

In cases like these our mind or ego tries to protect us by searching for equilibrium. If the information is at odds with our schema, we tend to find a middle ground and as such slowly let it filter through and change the preexisting category. As such, it does not come as a complete shock or surprise, and we don't feel distress.

This whole conflict is called cognitive dissonance, the feeling of acting in a certain manner not consistent with our personality. We may consider ourselves a moral person but then engage in an immoral act. This makes us feel at conflict, hence it is “dissonant” or not "congruent,” but we might find various ways of integrating this new aspect into a more holistic view of ourselves.

It is important to note that cognitive dissonance is not really a bad thing. It opens us to various truths about ourselves and our behavior. If you believe you are leading a healthy lifestyle but still smoke, you might need to change your smoking habits to fit into your own category of a healthy life-style.

What does being open-minded mean? I think it comes down to those points of accommodation and cognitive dissonance. People who are flexible enough and are ready to admit their errors, whether in logic or behavior, those to me are open-minded. They are ready to change their schemata and do not conveniently deceive themselves by holding onto false erroneous beliefs despite strong evidence to the contrary.