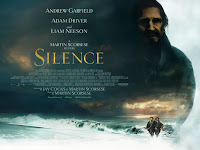

What makes Scorsese’s movie Silence (2016) brilliant is not what it states but what it implies.

Although many have hailed it as a testament to faith and by extension an

appraisal of Christianity and its values, the film offers more questions than

answers. If you approach it from different angles, you may spot troubling

messages regarding faith and religion.

The movie is set in feudal Japan where the government has

decided to ban Christianity and it is persecuting Christian missionaries

alongside many recently converted and faithful locals. Under the leadership of

the Japanese Inquisitor, the Christian priests and their followers are given a

chance to apostatize: If they stamp upon - and in other cases spit on - the

image of Christ, they shall be spared.

Various missionaries cannot do so and are ready to go

through immense suffering and to sacrifice themselves as martyrs, hence becoming

pillars of the Christian faith. Others break down and reject their religion to

continue living. When rumors hit the Vatican that the renowned head priest

Ferreira has apostatized and publicly denied the Catholic Church, two of his

idealistic disciples, two Jesuit priests reject this as mere gossip and hearsay

and decide to head to the dangerous territory to find out for themselves and

see it with their own eyes.

If they can prove that this were untrue or even better that

the priest had died for his faith, it would be a great boon for Christianity across

the world. The opposite, however, would destabilize the strength and fortitude

of the religion and plant seeds of doubt among its adherents. The Jesuit priests

soon realize that their religion has many persecuted followers among the simple

Japanese country people, many of whom are ready to die for harboring these

two priests.

Eventually and it was merely matter of time, both priests

are caught; one of them, Rodrigues ends up meeting his pale-faced mentor

Ferreira who in a cruel ironic twist of faith encourages his pupil to apostatize

as he has done. In fact, Ferreira has even acquired a Japanese name and

identity and is known for publishing anti-Christian writings. The world of the

young priest Rodrigues falls apart, and he ends up rejecting his faith publicly. On the other hand, the other priest Garupe, who was stricter and sterner in his beliefs,

dies in his attempt to save Japanese Christians.

All this set up provides us then with an important array of

thoughts and questions. First off, the most relevant one would be the problem

of evil: how can God allow his followers to suffer such torment and never

intervene on their behalf? Priests and Japanese Christians endure horrific

methods and sequences of torture and abuse by the hands of the Japanese, and it

seems that throughout all of this, God guards His silence.

In fact, the Jesuit priest Rodrigues claims he has not heard

God’s voice since youth and complains why He has not made himself heard to his

ardent worshiper. Doubts begin to fill his mind, and it is only towards the end

of the film where we seem to hear the voice of Jesus telling him that he was

there with this priest all this time suffering by his side. At the end of the

movie, the priest’s death is followed by Japanese funeral procedures but a

close-up reveals him secretly clutching onto his cross.

The ending can be interpreted as a reinforcement of faith

and that despite lifelong suffering and continuous eroding doubt, the priest

has never actually denied his faith. That is a valid reading; yet there is no

certainty in this. We do not see him arrive at the Gates of Heaven, which for

obvious reasons is avoided as it would reek of kitsch. In other words, we never

know whether all his pain and suffering was worth it and that his was indeed

the true religion.

One of the indications here would be the title itself:

Silence. This applies to an absence of not only sound but of God’s own

existence. There is a possibility, and this was the nagging doubt of our priest,

that his religion may be merely make-believe. There was doubt previously in

Scorsese’s masterful The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), but it

was overcome at the end as Jesus found himself back on the cross and died.

In that instance, we assume that Jesus preserved his faith

and managed to be resurrected as the Scriptures tell us. But again, this is an assumption that Scorsese

only implies; the music is joyful and celebratory but we never see Christ

actually go to heaven or resurrect with our own eyes. This is different from

Pasolini’s version of The Gospel

According to St. Matthew (1964), which for the most part has a documentary

feel to it but ends up showing us the after-effects of Christ’s death, the

trembling of the Earth and that he has arisen from the dead.

So we ask ourselves, how do we know if this religion is

true after all? Catholic religion has survived such a long time because of its

structure and philosophy. Belief in it is universal and standardized and is not

open to interpretation. It is beyond nationalities or ethnicity. It is run

internationally like an organization with its headquarters in the Vatican. This

is as true today as it was back then.

By way of comparison, the Protestant faith has not had such

a uniform run. Since many are open to voice their doubts, it has splintered

into many factions most of which do not see eye to eye with each other. It is,

for better or worse, not as solid and unified as the Catholic Church.

But the question remains, which is the true religion? What

if Catholics are wrong, and they are not adhering to the true religion? This is

a conversation the priest has with the Japanese Inquisitor. What if it turns

out that Buddhism is true after all? Is it not arrogance to blindly assume that

Christians are right and even conquer other countries in the process?

As the Inquisitor says, the Japanese have their own

religion, culture and beliefs, all of which they would like to preserve. So

with what right do these Christian missionaries come and usurp their territory?

In that sense, we can see the political workings and machinations of religion.

It is not merely a matter of faith but cuts much deeper than that.

The priest responds that Christianity is beyond nations and

borders because it is the truth. But why did it then not firmly set foot in

Japan? Because the Japanese soil is rotten and truth cannot grow there, this is

the young priest’s weak answer to that question. Suddenly, we realize that the

Japanese are not driven by sadistic motives but that they try to preserve their

culture and traditions, all of which they perceive being under attack by the Christian

threat.

The arrogance of the Catholic Church can also be felt in its

methods of punishing sinners and non-believers. This is not touched upon in the

film but as I was watching the Japanese torture of the Christians, I could not

stop thinking of the horrendous and horrific ways that Inquisitors of the Holy

Church had tortured and tormented so many souls. What if all of this was in

vain, and these people suffered and died meaninglessly by the hands of the

priests?

Of course, the priests believed that they were doing a

favor to their victims as they were supposedly cleansing all their sins

through immense and imposed suffering and that the souls of their victims would

be free to enter the Pearly Gates. But that seed of doubt is the issue here,

what if it is not true? Then these people had been brutally killed for nothing.

Yet apart from being a usurping power, did the priests truly

manage to conquer the hearts and minds of this country folk? The head priest Ferreira

says no. These people in their simplicity and due to their previous cultural

beliefs and upbringing had a faulty understanding of the Christian faith. In an

earlier scene of baptism, we witness how a young couple assumed that they were

all in heaven after their child was baptized, and the Jesuit priest had to

correct their views and say that this was not so and that paradise was another

place indeed.

Furthermore, the Japanese had the belief that the sun was

Jesus and that he did not arise three days later but every day instead. Such

misunderstandings and misinterpretations led these people to follow a religion

that was neither Christianity nor their own cultural belief but rather a hybrid

of both. In that sense, the missionaries had effectively failed propagating the

true religion instead giving birth to something else completely.

That is another issue that arises. Since each and everyone

sees and interprets the world in a different manner, how can one have universal

beliefs then? And how do we know that they are all aligned? Even among priests

there are discrepancies, and they draw their ideas and inspirations from the

Holy Book, which has contradictions itself and can be interpreted in a variety

of ways. Which is the truth after all? On this essential question, the movie

remains uncomfortably silent.

3 comments:

I find that your review is very personal. The questions you ask of the movie, which you find it silent upon, aren't my questions; not now, at any rate. What I would like to ask you, as a favour & supplemental to your review, is whether the movie is good entertainment, and if so, of what kind? That is, cinematically. I liked Liam Neeson in Schindler's List, but since then he seems to have gone in for hyper-violent roles (Taken, etc) where his character is prepared to kill indiscriminately.

And I would also like to feel that a movie revolves round an established sense of moral goodness, whose absence is recognizable and regretted.

I suspect that Silence, therefore, is not my kind of movie at all; and don't want to impose any burden upon you of more than the briefest response, e.g. "You might like it" or "no, you definitely wouldn't like it!"

Your question is one of the toughest to answer and again I'd have to resort to personal answers / opinions. Silence can be seen as the unofficial final leg of Scorsese's trilogy of faith: the first one and by the far the best in my opinion is The Last Temptation of Christ, followed by (the rather bland, again my opinion) Kundun, while Silence falls somewhere in-between.

I generally like films that deal with faith and although it is generally good I would not say it is the best film out there. In comparison, I much preferred the quirky There will be Blood (although that one I appreciated much more after the second viewing) and remember being impressed by The Master, both by the great P.T. Anderson!

As to Liam Neeson I liked him of course in Schindler's List best. Here he has more of a supporting role and he's good, not great in it. I have only seen the first installment of Taken and thought he was great in a so-so movie because it was interesting to see his range, especially at his age.

Now I notice that the answer has not been brief, so I will say this much: I do not think it is a must-see but you could give a try. As my review shows, don't be discouraged by its Christian bent and content because Scorsese provides enough leeway for other interpretations as I hope my post demonstrates.

Thanks for taking the trouble, it's very helpful. I very much liked The Last Temptation of Christ, but more on account of Kazantzakis' agenda than Scorsese's methinks. This comes across most clearly when reading the book, which, brilliant as it is, endlessly presents a two-way pull between spirit and flesh. I can only take it in small doses. Spirit v. flesh not being my battle & faith (in the sense of belief that one clings to) even less.

Post a Comment